This article is based on a session at ATypI 2025 Copenhagen– Toward Inclusive Typography: Revitalizing Taiwan’s Native Languages Through Type.

Picture this: You’re designing a font, and someone mentions they want to support “Taiwan.” Your mind immediately jumps to traditional Chinese characters—thousands of intricate strokes, years of work, and a daunting technical challenge. But here’s the thing: that’s just the tip of the iceberg.

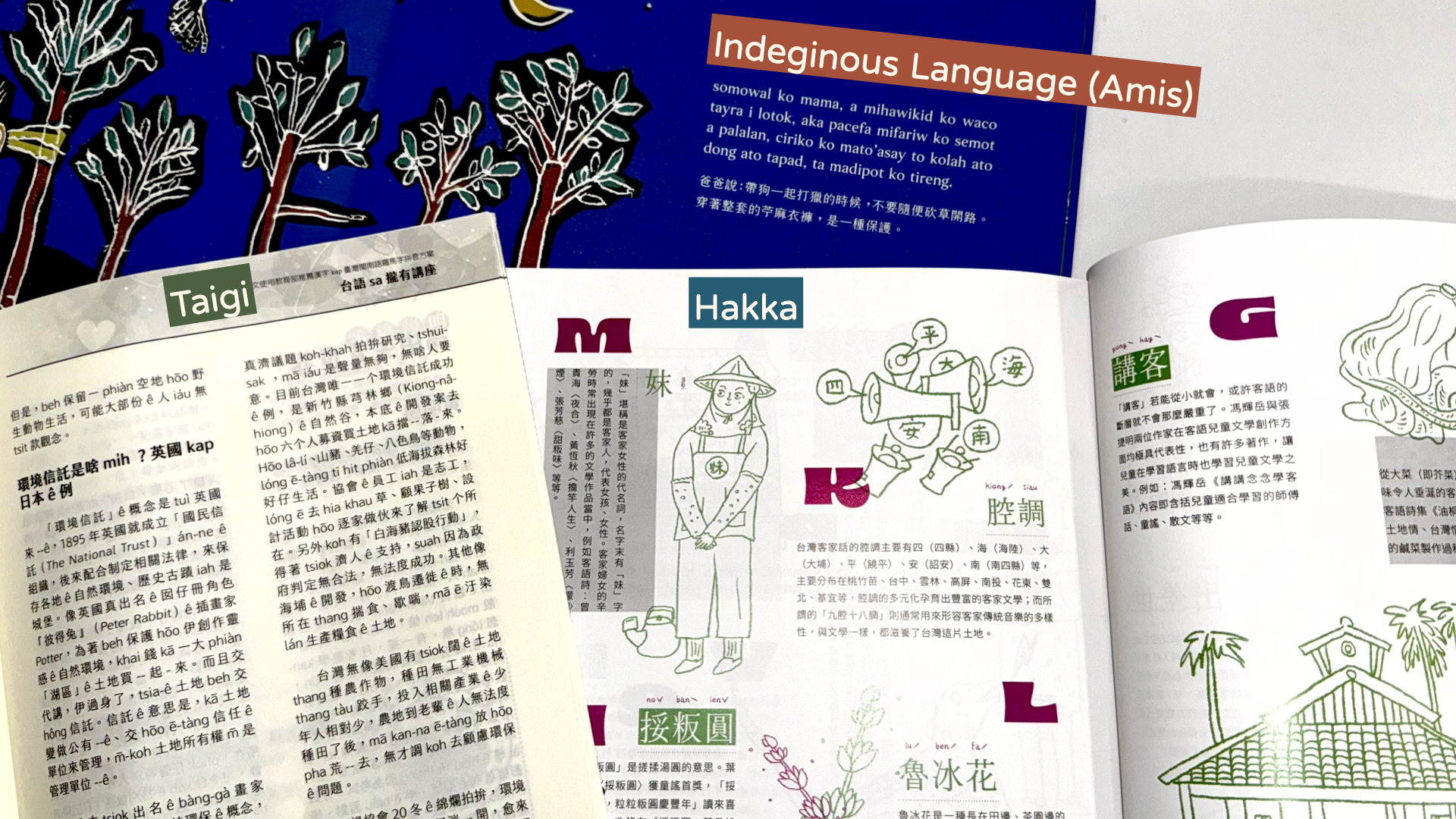

Taiwan is home to over 20 living languages, and many of them don’t require a single Chinese character. In fact, some of the most vibrant linguistic revival movements happening on the island right now rely largely on extended Latin alphabets—letters you probably already know, just with a few extra marks and characters. Although languages like Taigi and Hakka can also be written in Hanzi (Chinese characters), the Big5 encoding system omitted many characters necessary for these languages, whether they’re written in Latin scripts or Chinese characters.

So before you write off supporting Taiwan’s linguistic diversity as “too complex,” let’s take a journey through this fascinating typography landscape that most of the world never sees.

A Quick Reality Check About Taiwan’s Languages

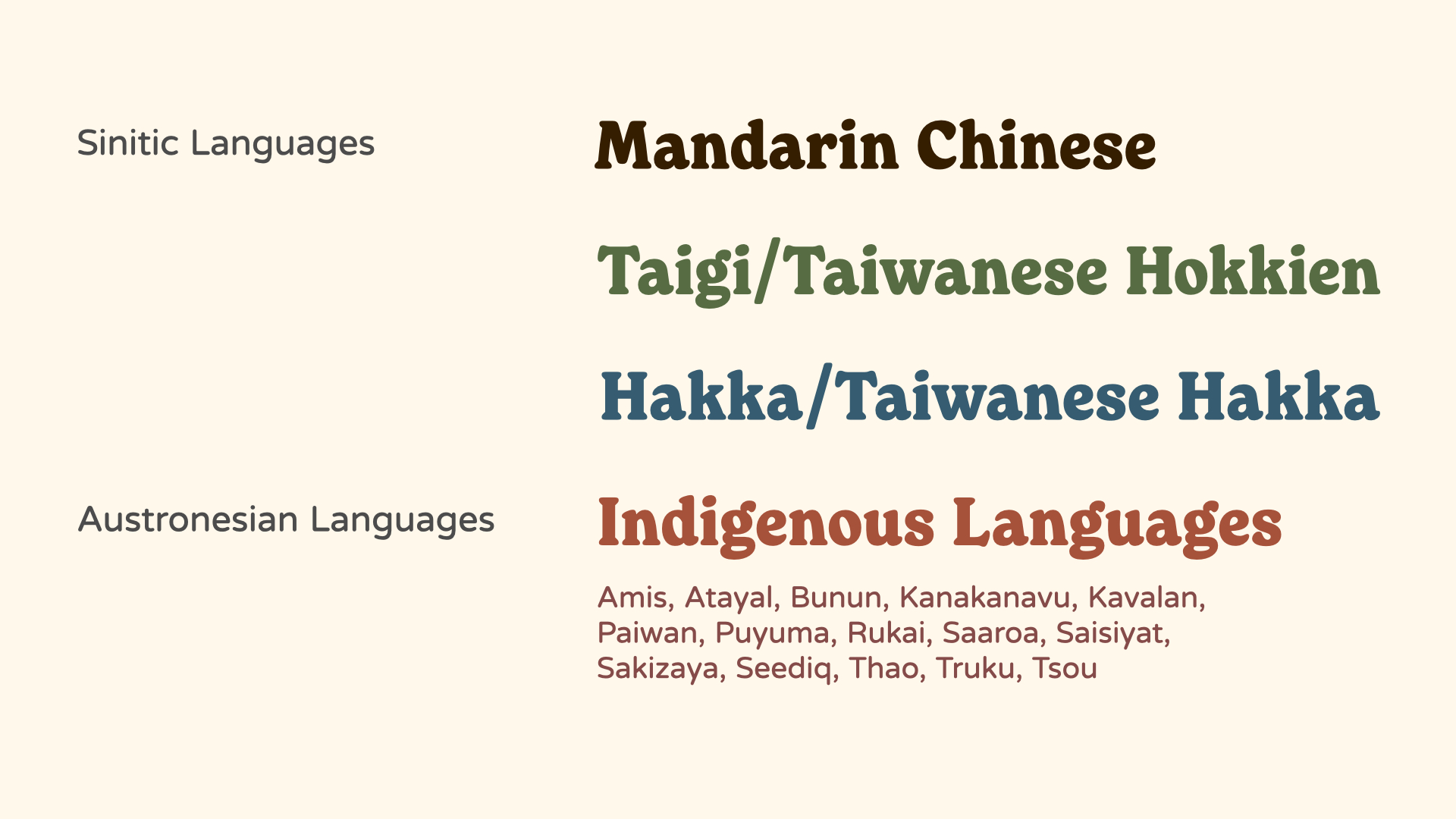

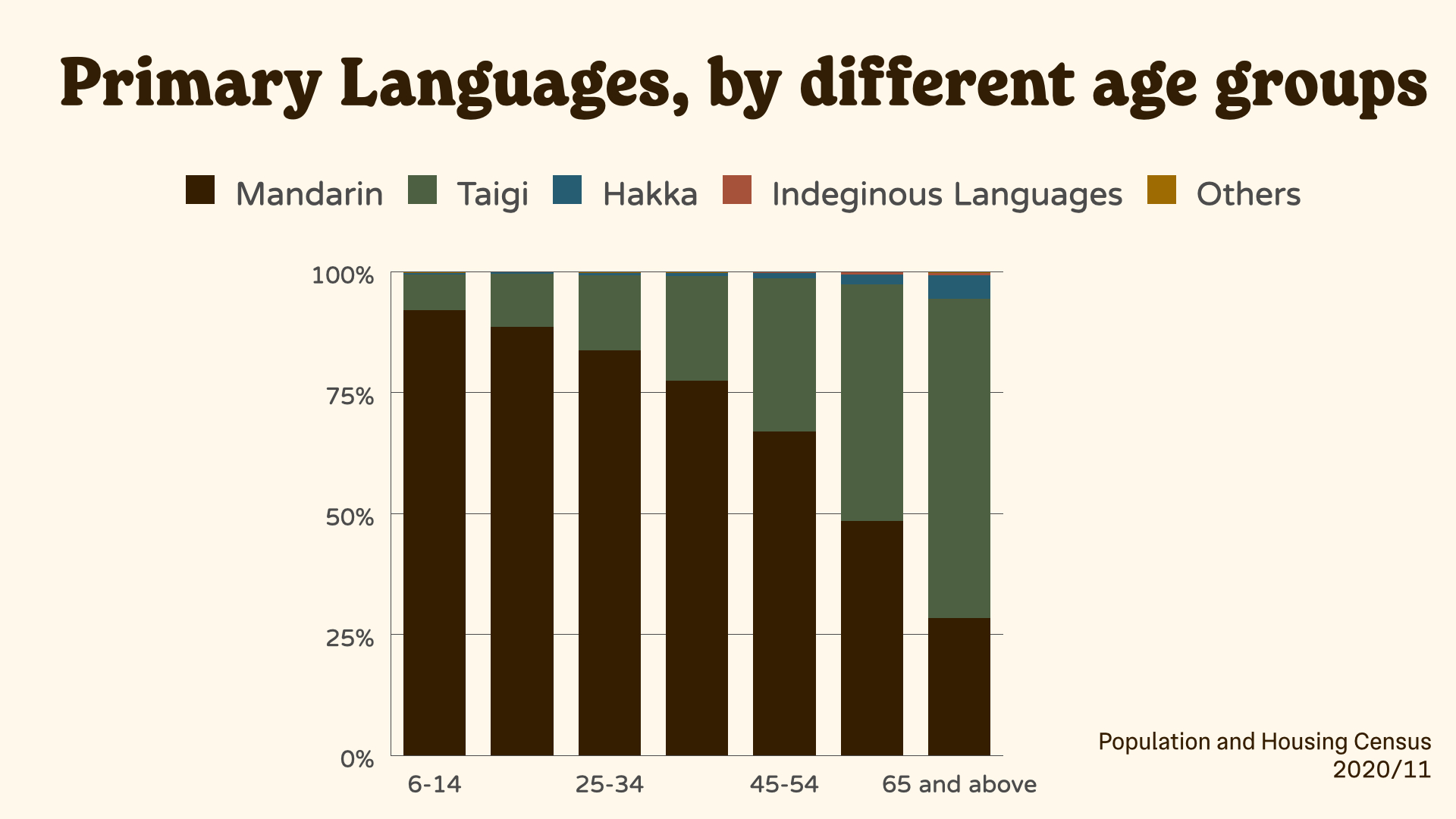

When most people think of Taiwan, they picture traditional Chinese characters and maybe hear some Mandarin. But Taiwan’s linguistic reality is far richer and more complex:

- 16 officially recognised indigenous languages: all written in Latin scripts

- Taigi: spoken by 70% of the population, can be written in Latin, Hanzi characters, or a mixture of both

- Hakka: written in Latin, Hanzi, or mixed

- Mandarin: primarily Hanzi characters

- Plus several other regional varieties

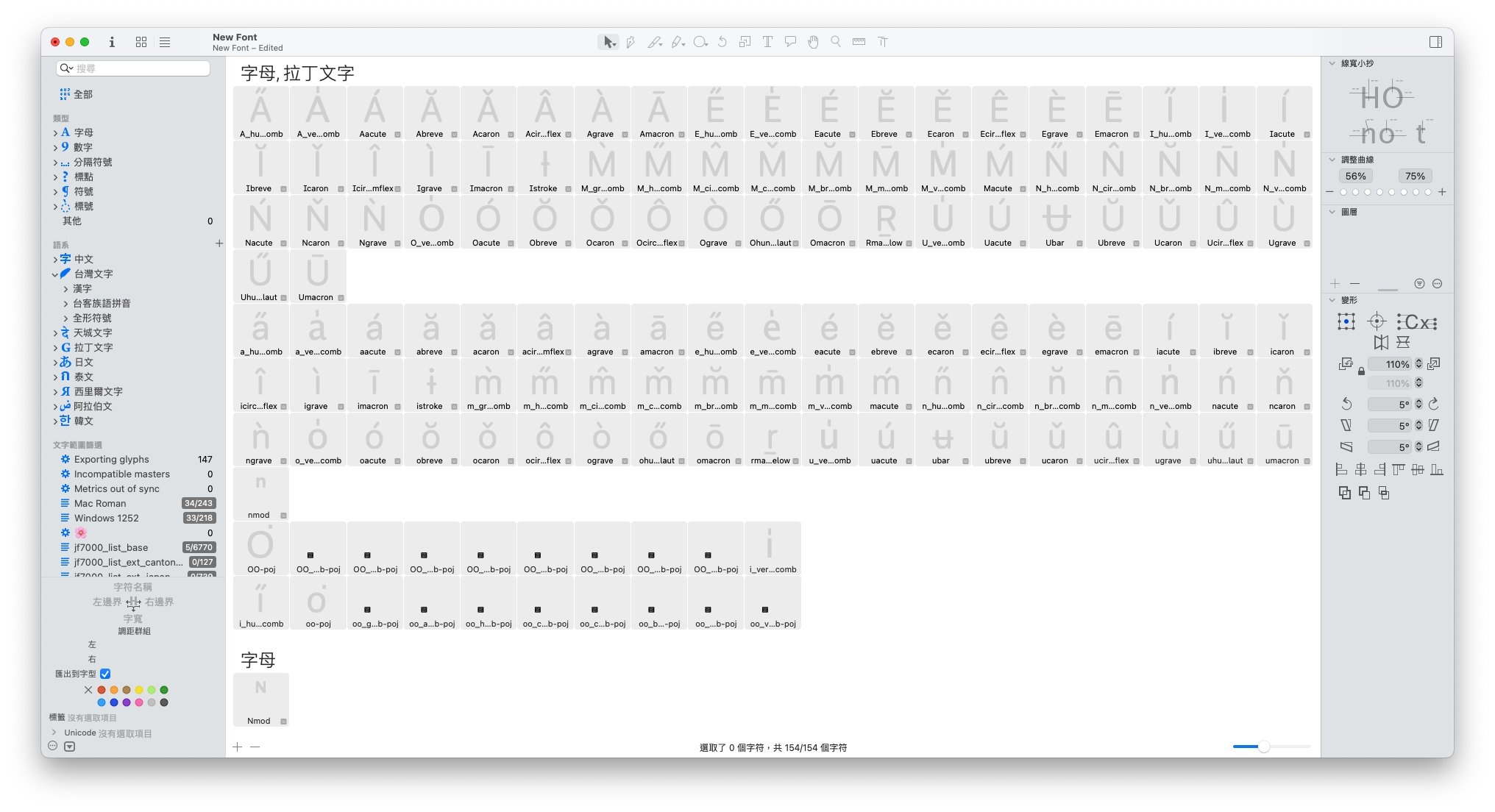

What’s fascinating is that the recent jf7000 character set project specifically includes a “Formosan Languages Pack” that references indigenous writing systems, Taigi, and Hakka romanisation alongside common Hanzi characters. This shows how typography projects are finally recognising that supporting Taiwan means supporting multiple writing systems, not just Chinese characters.

The Latin Revolution You Probably Missed

Here’s where it gets interesting for font designers: Taiwan’s Indigenous languages all use Latin-based alphabets, building on romanisation systems that can be traced back to the Dutch East India Company (VOC) colonising southern Taiwan in the 17th century and other Western influences. Taigi has been written in a Latin system called Pe̍h-ōe-jī (POJ) since the 19th century, developed by Western missionaries.

This means that a significant portion of Taiwan’s linguistic diversity can be supported by extending your Latin character set—something far more approachable than designing thousands of Chinese characters.

Think of it this way: instead of spending 2-3 years creating 13,000+ Chinese characters, you could support multiple Formosan languages by adding at most 168 additional Latin glyphs—specialised characters and diacritical marks that cover all the romanised writing systems used across Taiwan. The impact-to-effort ratio is extraordinary.

The Political Silencing of Languages

To understand why typography challenges exist, we need to acknowledge Taiwan’s complex colonial history. Different ruling powers had varying approaches to local languages, creating the foundation for today’s digital inequalities.

During Japanese colonial rule (1895-1945), the situation was complex. While Japanese became the official language, the colonial government valued Formosan languages (Indigenous languages, Taigi, and Hakka), though they seemed to them as a channel of governing. They published dictionaries between Japanese and these languages, people continued writing in Pe̍h-ōe-jī, and colonial officers learned local languages. Systematic suppression of local languages didn’t intensify until the militaristic period of the 1930s, when Japan began preparing for war.

.jpg)

The more severe linguistic oppression came after World War II, when the Republic of China government arrived and enforced Mandarin everywhere—schools, media, and official documents. The policy of banning first languages wasn’t softened until the late 1980s, and the National Development of Languages Act didn’t actually begin implementation until 2019.

This political suppression created generations who couldn’t speak their ancestral languages. The result? A linguistic landscape where Mandarin dominates among younger generations, while Formosan languages struggle for survival. When digital technology emerged, it naturally followed the dominant language patterns, leaving minority languages behind.

When High-Tech Society Meets Low-Tech Languages

But here’s where things get frustrating for speakers of these languages—and why Taiwan’s situation is particularly ironic. Taiwan is one of the world’s most digitally advanced societies, home to tech giants like TSMC and a population that lives practically everything online. Yet this hyper-digital environment makes language barriers even more exclusionary than before.

In a society where digital devices are used for everything from ordering food to accessing government services, not being able to type in your native language isn’t just inconvenient—it’s digitally disenfranchising. When your grandparents’ language can’t be appropriately displayed on your smartphone, or when social media platforms mangle your cultural expressions, you’re effectively cut off from full participation in modern Taiwanese life.

The Encoding Boundaries

Despite being official national languages since 2019, Formosan languages continue to face digital discrimination. The legacy Big5 character encoding system, developed during the period of language suppression in the 1980s, never included key characters needed for these languages.

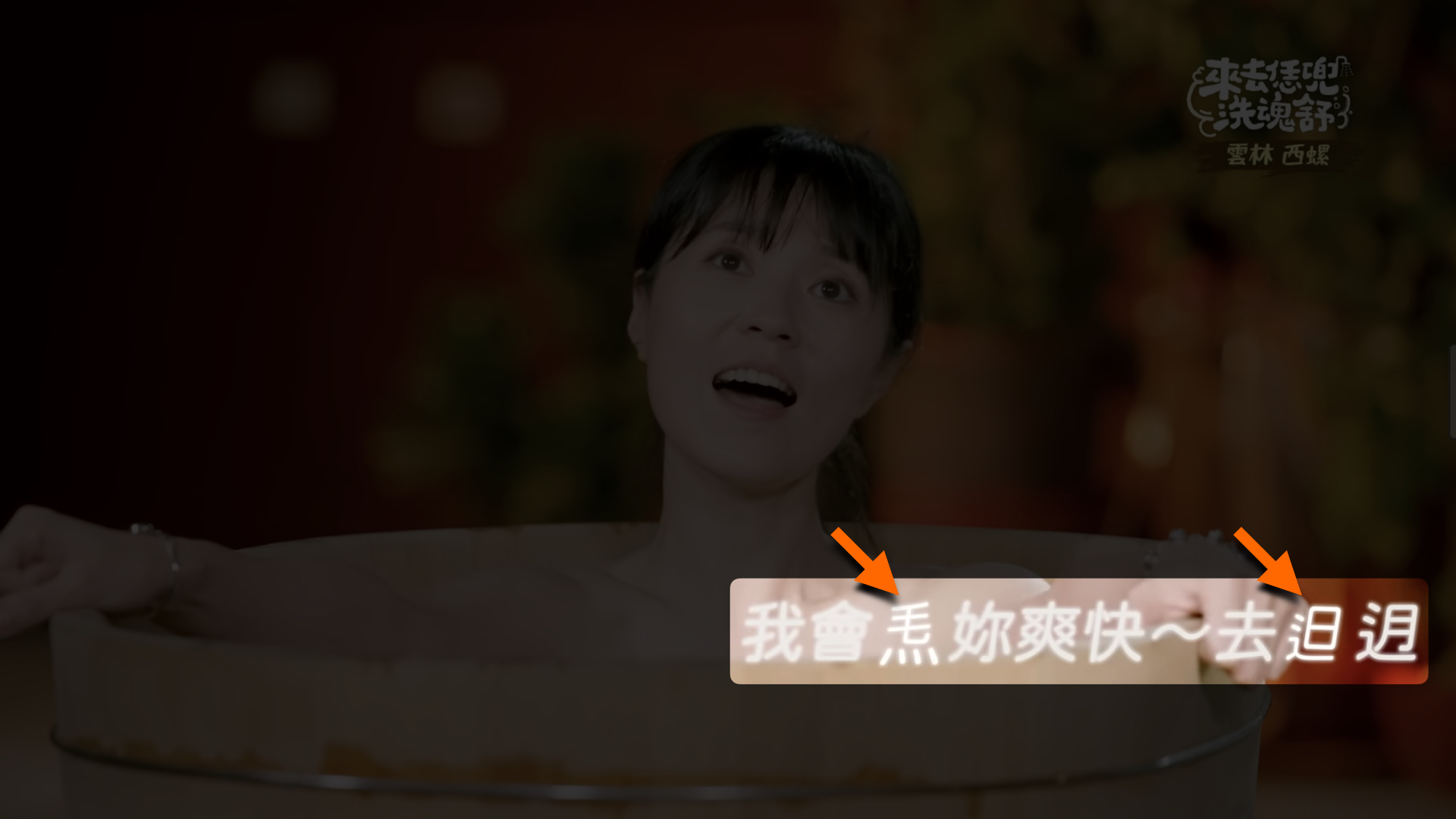

The result? You get situations like this recent TV show in Taigi where fonts randomly switch mid-sentence because the broadcaster’s system couldn’t handle certain characters. Users had to resort to creative workarounds and encoding hacks, creating what became a “digital Tower of Babel” where different systems used incompatible methods to represent the same languages. This encoding chaos made information transfer between systems nearly impossible.

Even today, with Unicode theoretically supporting these characters, they were encoded across different areas over a 30-year span, making it hard for system providers and type designers to keep up with the latest requirements. Unicode now includes the Hanzi characters for Formosan languages suggested by Taiwan’s Ministry of Education, though this doesn’t cover all possible characters these languages might need. The infamous “tofu” characters (those little boxes that appear when fonts don’t support a character) are frustratingly common for users of Taiwan’s diverse languages.

Software That Doesn’t Get It

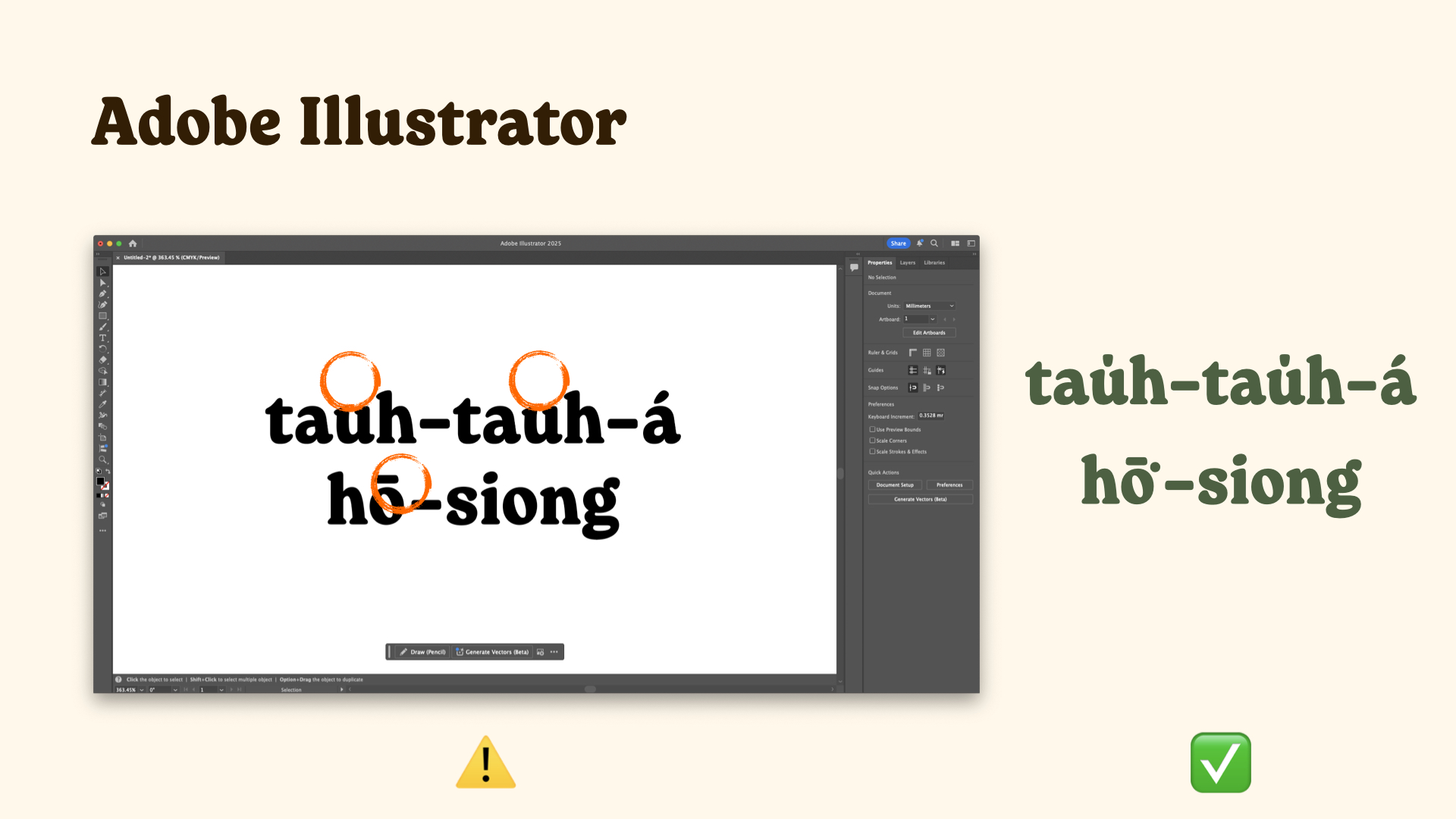

The typography challenges go beyond character sets. Standard design software often assumes you’re working in “mainstream” languages:

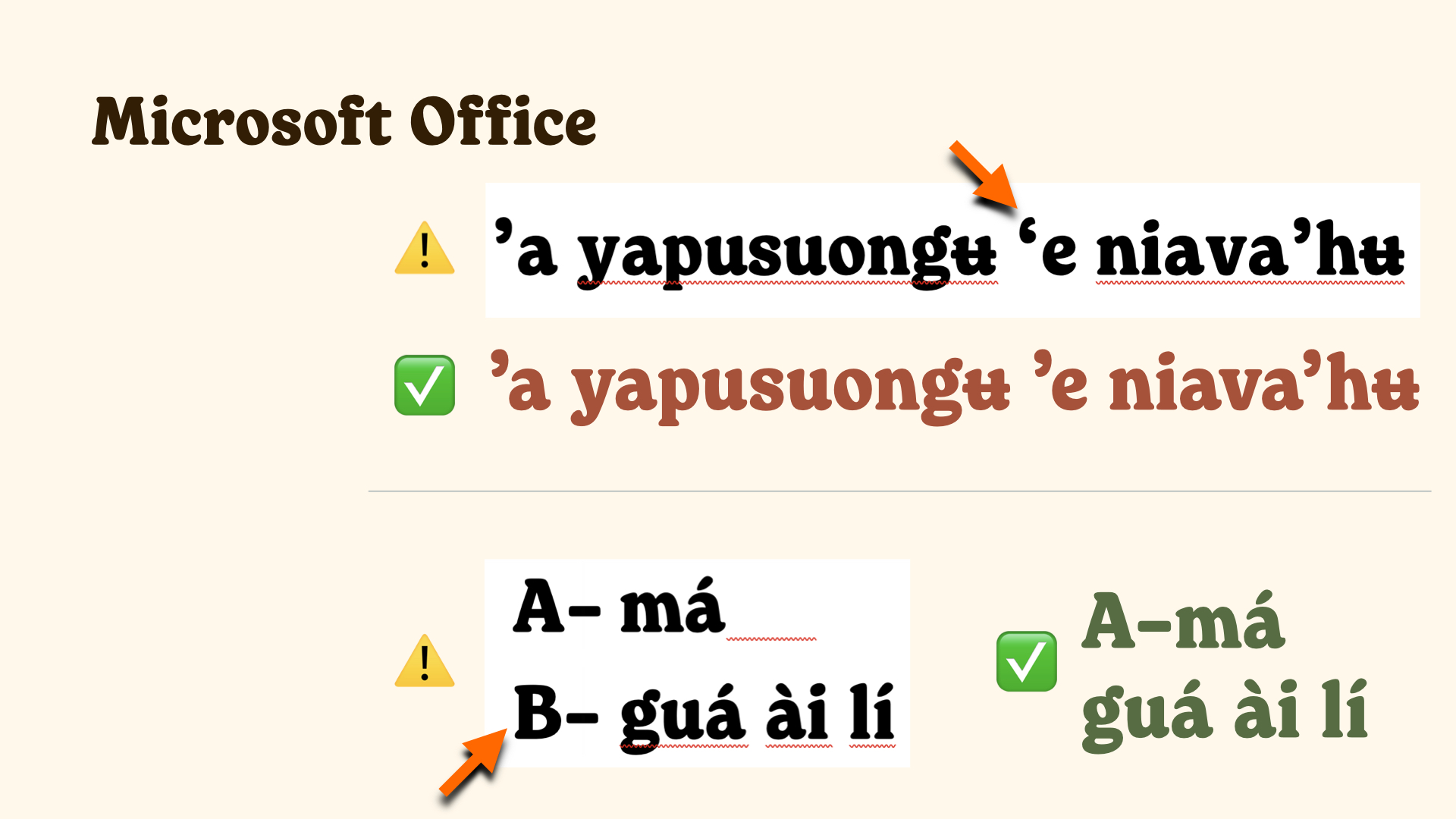

- Autocorrect systems constantly “fix” indigenous language words, treating them as typos

- Adobe Illustrator drops diacritics from Taigi text by default

- Word processors apply inappropriate typography rules designed for other languages

The current solutions are far from ideal—disable autocorrect (losing convenience), switch to obscure menu options that might break other elements of your design, or just accept broken typography.

The Game-Changers Making It Happen

Despite these challenges, an inspiring community of designers and developers is pushing boundaries. Projects like “No Tauhu” (conducted by a student) and the jf7000 character set offer updated encoding information for all of Taiwan’s diverse writing systems.

But Ko, the designer behind the open-source Iansui font (now available on Google Fonts), has devoted himself to supporting Formosan languages through typography. His Glyphs script helps filter out the various language glyphs and render diacritics properly—it’s a game-changer for type designers.

The jf7000 project itself represents a new approach: instead of requiring designers to create massive character sets, it provides a core set of about 7,000 commonly used traditional Chinese characters, with extension packs including the “Formosan Languages Pack” that covers indigenous languages, Taigi, and Hakka, that designers can add as needed.

Why This Matters (Beyond Taiwan)

Taiwan’s situation isn’t unique—it’s a case study in how colonialism, political suppression, and technological development can marginalise languages. With more people unable to speak their ancestral languages, and several indigenous languages already extinct or moribund, typography becomes a tool of cultural preservation.

But there’s something hopeful happening. Recent years have witnessed how character sets and font support can help preserve and revitalise Formosan languages, with dictionaries, social media apps, and news channels flourishing when the technical barriers are removed.

Think of typography not just as visual design, but as cultural infrastructure. When someone can type their grandparents’ language into their phone, share poems in their native script on social media, or see their language properly displayed on TV, you’re not just solving a technical problem—you’re enabling cultural continuity.

Your Entry Point: Start with Latin

If you’re a designer intrigued by this challenge but intimidated by the complexity, here’s your starting point: the Latin extensions.

Supporting Taiwan’s Indigenous languages, Taigi and Hakka romanisation doesn’t require learning Chinese typography principles or designing thousands of characters. You’re working with familiar Latin letterforms—at most 168 additional glyphs to cover all romanised Formosan languages—with careful attention to diacritical marks.

Projects like jf7000 have done much of the research work, identifying exactly which characters and combinations are needed for Formosan languages. The community surrounding multilingual typography in Taiwan is also remarkably welcoming to newcomers who wish to contribute.

A Typography Movement, Not Just Fonts

What’s happening in Taiwan represents something larger: typography as a form of decolonisation. After decades of having their languages marginalised, communities are reclaiming their linguistic heritage—and they need fonts that work.

Since jf7000’s launch, it has received valuable feedback from diverse communities, with fan groups adding characters for K-pop stars’ names and professionals contributing missing characters for specialised fields. This demonstrates how typography projects can evolve into community endeavours that serve needs far beyond what designers originally envisioned.

The technical challenges are real, but they’re not insurmountable. The cultural stakes, however, are enormous. Languages that took thousands of years to develop can disappear in a generation if they lack digital support.

Making Typography for Everyone

Taiwan’s journey with multilingual typography is just beginning, but it offers a blueprint for designers everywhere working with minority or indigenous languages. The lesson isn’t just about Taiwan—it’s about recognising that behind every “minor” language or “special character request” is a community trying to maintain their cultural identity in the digital world.

So the next time someone asks if your font supports Taiwan, remember: it’s not just about traditional Chinese characters. It’s about a rich linguistic ecosystem that has been fighting for recognition and revival. And supporting it might be more achievable than you think.

Typography isn’t just aesthetics—it’s about language, culture, and identity. Sometimes, it helps reclaim what was almost lost.

This article is written based on the session at ATypI 2025, with the help of Claude.